Years ago, I read an article on the psychoanalytic view of empathy. The author defined empathy as: the analyst’s feelings when in the presence of the patient.

It is certainly important for therapists to be in tune with our feelings during therapy—that can be an important source of information about what’s going on in the therapeutic relationship, especially when there’s some tension in the room.

This definition of empathy is misguided and almost delusional, because your feelings (if you are the therapist) can be extremely misleading. Our feelings during therapy sessions are never caused by the patient, but rather our own thoughts.

And our thoughts are sometimes distorted and completely out of touch with how the patient is thinking and feeling. I’ll give you a couple striking examples of how I missed the boat when I jumped to conclusions about how my patients were feeling based on how I was feeling.

Example 1

During an inpatient cognitive therapy group at my hospital in Philadelphia, I was working with a severely depressed woman named Lucretia who had experienced two traumatic events in the same week. On Monday, her husband walked out on her, and on Tuesday she lost her job. She felt hopeless and suicidal, and was telling herself that she was a worthless human being.

During the group I showed Lucretia how to talk back to her negative thoughts, and she seemed to be feeling much better by the end. In fact, I thought I’d done a fantastic job.

At the start and end of each group, I ask all the patients to complete my Brief Mood Survey (BMS), so I can see how severe their symptoms are and how much they’ve improved during the group. It takes them about a minute. At the end of each group, I ask them to complete the BMS again and to rate me on several scales that assess empathy and helpfulness. Because the scale asks patients how they’re feeling “right now” you can see how effective you were by comparing the scores at the start and end of a group or individual therapy session.

I expected glowing ratings from Lucretia but was shocked to discover that her depression and suicidal urges had gotten much worse over the course of the session. In addition, she gave me the lowest scores I’ve ever seen on the empathy and helpfulness scales. Clearly, my feelings in the presence of the patient had NOT been a reliable source of information about how my patient was feeling.

I was perplexed and convinced that she’d made a mistake when filling out the forms, so I asked her to review her answers to make sure they were correct. Sometimes, people get confused by the response options and fill out the scales in the opposite way they intended.

Lucretia glanced over her answers and said, “There’s no mistake here, Dr. Burns.”

I said, “What do you mean? We just had a terrific session!”

Lucretia responded, “Terrific for you, maybe!”

I asked what she meant. She explained that when I said she’d had a double whammy—losing her job and husband at the same time—she’d thought I was making fun of her, since “double whammy” sounded like a phrase in a comic book.

I had no idea that she’d reacted so negatively to my comment. Fortunately, we had a good talk and quickly resolved the problem, but if I hadn’t used the assessment tests, I would have been totally deceived into thinking I’d done a terrific job.

This was a classic example of a common cognitive distortion—Positive Mind-Reading- when you assume, without good evidence, that others have far more positive feelings about you than they really do. I’ve been fooled by Negative Mind-Reading as well.

Example 2

At the start of the inpatient group the next week, I noticed that a newly admitted patient named Rose was feeling extremely depressed, anxious, and angry. She’d just been hospitalized involuntarily because of a failed suicide attempt the night before, and she’d just been transferred to the psychiatric unit from the intensive care unit. She defiantly announced that she intended to complete the job and take her own life at the first chance she got.

Rose explained that she’d been treated for depression for years, but nothing had ever helped, and she felt horrible every minute of every day. She said that she’d struggled with a crack cocaine habit and had been living in a recovery house in Philadelphia. She’d been clean and sober for two months but slipped up and used crack following an argument with her roommate. The staff threatened to kick her out of the program, so she got mad and tried to kill herself. She said she felt utterly worthless and had decided it was time to face the facts about her life and cash it in.

I asked how many of the other patients in the group sometimes felt worthless and hopeless, or even suicidal. Every hand went up. I asked Rose if she’d like some help during the group, and if she’d ever been treated with cognitive therapy.

See also: Comparing ACT and CBT: Defusion vs. Restructuring

She practically bit my hand off and said I sounded like every other stupid effing shrink she’d wasted time with and loudly announced that she had no interest whatsoever in any of my effing cognitive therapy.

I felt about two inches tall and decided that Rose wasn’t going to be the most motivated patient to work with during the group. I backed off and worked with a woman on the other side of the room who also felt hopeless and worthless. Rose didn’t utter a word the entire time. I was afraid to look in her direction but could sense that she was staring at me with daggers in her eyes. My feelings told me that she was intensely angry with me.

We had a reasonably good group, but I dreaded having to review Rose’s feedback at the end of the session. I was taken aback when I saw that her scores on the Depression, Suicide, Anxiety and Anger scales had all fallen to zero, which indicates a complete elimination of symptoms. I was even more surprised to see that she’d given me perfect scores on the empathy and the helpfulness scales.

At the bottom of the feedback form, patients describe how they felt about the group. For the section on “what did you like the least about the group,” Rose had simply written, “Nothing.”

For the section on “what did you like the best about the group,” she wrote:

Dr. Burns, when you worked with that other woman, I felt like you were working with me. Her negative thoughts and feelings were just like mine. I’ve never had cognitive therapy before, and I didn’t even know what a cognitive distortion was.

I always thought my problem was that I really was a worthless and horrible human being, but now I see that the real problem is the way I’ve been thinking, and I can see how distorted and unfair my negative thoughts have been.

I can hardly believe I’m saying this, but I’m feeling joy and self-esteem right now. In fact, this is the first happiness I’ve experienced in my entire life. Thank you so much! The last hour and a half has changed my life.

Sincerely, Rose

If I hadn’t been using the assessment tests, and had relied on how I was feeling, I wouldn’t have known that the group had been so helpful to her, and probably would have gone out of my way to avoid making eye contact with her if I saw her on the psychiatric unit. In this case, I was fooled by Negative Mind Reading.

I’ve chosen two dramatic examples of how our perceptions of how our patients feel, and how they feel about us, can be way off base. These kinds of errors are not unusual, but common. My research indicates that therapists’ perceptions of how their patients feel, on average, are typically less than 10% accurate. If you ask patients, “How are you feeling right now?” and you ask therapists the exact same question, “How is your patient feeling right now?” the therapist’s answer will too often be way off base.

I define empathy differently from the way the psychoanalyst described it. To me, there are three parts to empathy.

-

If asked, your patient will say that you know exactly how she or he is thinking. I call this “Thought Empathy.”

-

Your patient will also say that you know exactly how she or he is feeling. I call this “Feeling Empathy.”

-

Your patient will say that she or he trusts you and feels accepted and cared about.

So how can we improve our empathy for our patients? One excellent solution is to use assessment instruments at the start and end of each session, like the ones I described above. It takes a lot of courage, but the information can be illuminating, and in some cases life-saving. If you’re interested in learning more, you can check out my Therapist’s Toolkit.

You also need to learn how to respond to the many failures you will discover when you use these assessment instruments for the first time, so you can transform your failures into therapeutic breakthroughs.

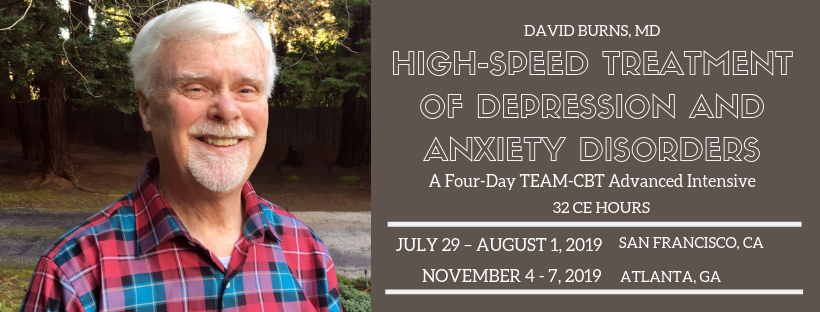

Join Me. Learn & Master Many New Techniques to Boost Your Clinical Effectiveness