by Kevin Polk, PhD, and Benjamin Schoendorff, MA

The key to psychological flexibility and valued living is noticing the difference between five senses and mental experience and noticing the difference between moving toward who or what is important versus moving away from unwanted inner experience.

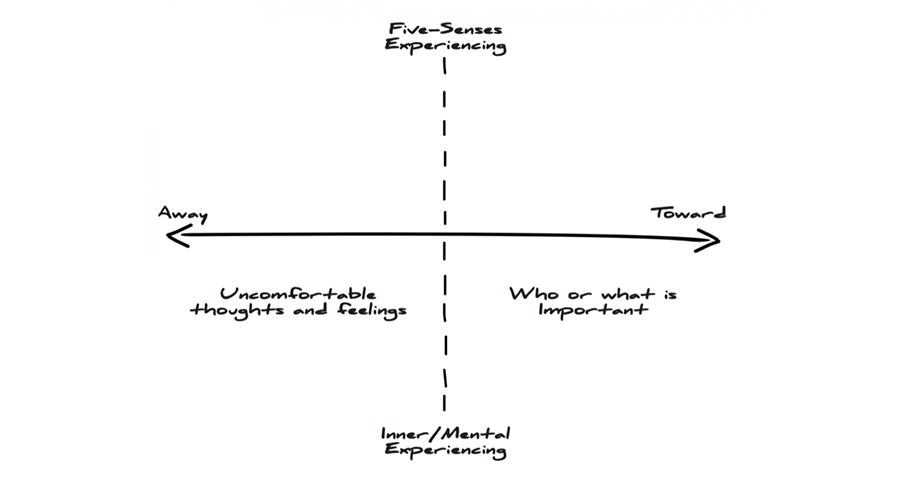

The matrix is a diagram about noticing—a diagram that can, as it turns out, cue psychological flexibility. It’s composed simply of two bisecting lines: the vertical line representing experience and the horizontal line representing behavior.

The vertical line maps out the difference between the aspects of our experience that come through our five senses—vision, hearing, smell, taste, and touch—and the part of our experience that arises from our mental activity, or interoceptive abilities. As you read this sentence, see if you can notice the part of your experience that comes through your five senses: the color of the screen and the font, the shapes of the letters, and so on. Now see if you can notice the mental part of your experience: the meaning of the sentence, perhaps some thoughts about where is this leading, and so forth. Do you notice a difference between these two types of experience?

The horizontal line maps out the difference between actions aimed at moving away from unwanted experience (for example, moving away from fear) and actions aimed at moving toward who or what is important (for example, moving toward a loved one). Take a moment now to recall a time when you did something to move away from fear, and then a time when you did something to move toward a loved one. Do you notice a difference in how it felt to move away and how it felt to move toward?

Do you notice a difference in how it felt to move away and how it felt to move toward?

The ACT matrix invites us to sort our experiences, behavior, and stories into the four quadrants formed by the two bisecting lines.

We all have a story to tell—a collection of interesting memories. And in the same way that any memory can be sorted into the categories of the matrix, a life story can also be sorted into the matrix using the four areas created by the two crossed lines. For many people, relationships come first, so we often begin by asking “Who is important to you?” And then, “What is important to you?” The answers to those questions go in the lower right of the diagram because their importance is in the mind (rather than through the senses) and people want to move toward (rather than away from) them.

A key part of the story is the stuff that can show up inside, and get in the way of, moving toward who or what is important. Maybe it’s the fear that shows up when thinking about asking someone out on a date. These experiences get sorted into the lower left quadrant because they are inner experiences that we tend to want to move away from.

The story also includes behaviors that everyone can see: walking, talking, sitting, and such. These go into the upper two sections of the diagram. First, we ask about the behaviors done to move away from unwanted experience, like running away from fear. These are sorted into the upper left quadrant. Finally, we ask about the behaviors that are done, or could be done, to move toward who or what is important. These are sorted into the upper right quadrant.

Sorting on the matrix can help all of us conceptualize our life and notice whether what we do tends to be more in the service of moving toward or moving away. Based on what we notice, we can choose to change our behavior as needed to move toward what we most care about.

People get stuck when their attempts to move away from unwanted inner experience keep them from doing what’s important to them. It’s often more useful to look at psychopathology dimensionally—in terms of the extent to which people get stuck, and in which domains—rather than categorically, with a focus on which precise kinds of inner experience or behavior cause them to get stuck. In this way, the matrix supercharges the transdiagnostic nature of acceptance and commitment therapy by providing practitioners and clients with a common frame of reference: two bisecting lines on a piece of paper.