The following excerpt is from Learning ACT, 2nd edition, by Jason B. Luoma, PhD, Steven C. Hayes, PhD, and Robyn D. Walser, PhD

A big difference between acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and most other treatment approaches is the treatment of human suffering.

Many treatment approaches begin with an assumption that negatively evaluated thoughts and feelings—for example, anxiety, depression, obsessions, or delusions—are problems to be gotten rid of. In contrast, in ACT these unwanted thoughts and feelings are not regarded as primary treatment targets. Rather, attempts to avoid these unwanted private events are seen as dysfunctional in that avoidance behaviors are often dysfunctional and can prevent the client from experiencing desired life consequences.

See also: Obstacles to Committed Action: Experiential Avoidance

The ACT model of suffering suggests that difficult thoughts and feelings are an inevitable aspect of human existence rather than problems to be gotten rid of. Life includes painful events. Attempts to avoid pain tend to magnify the pain rather than eliminate it (Hayes et al., 1999, pp. 60–62).

ACT focuses on the individual’s behavior and the context in which it occurs. Therefore assessment is focused on the presenting problems of the client while considering that person’s past and current environment.

Moving Toward Successful Working

The outcome criterion of ACT is “successful working.” This means that the goal of ACT work is to get the person’s behavior to work successfully, according to that person’s values and desired ends and in that person’s current context, given all the experiences that person had before then.

This is in contrast to the more mechanistic medical model, in which assessment emphasizes assigning diagnostic labels and has symptom reduction as the primary outcome criterion. For example, assessment and treatment for anxiety under the medical model might emphasize exploring contexts in which anxiety occurs for the purpose of assigning a diagnosis, for example, social anxiety disorder versus generalized anxiety disorder. After the diagnosis is decided, the practitioner then prescribes medication to reduce anxiety or uses cognitive restructuring (that is, replacing irrational beliefs with more rational ones) with the goal of decreasing anxiety.

In contrast, an ACT therapist might assess contexts in which anxiety occurs and what the client does when feeling anxious. For example, does the client avoid or escape anxiety? The functions of anxious behaviors, for example, avoiding certain situations or performing rituals to minimize or avoid anxiety, take center stage in ACT clinical work.

The centrality of these functions in ACT renders the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnostic categorization relatively unimportant. (Of course, the DSM remains a practical tool for communication with other professionals and in working with third-party payers.) Instead of regarding decreased anxiety as the only desirable outcome, ACT treatment emphasizes the client changing her relationship to anxiety in order to function more effectively in contexts where avoiding or escaping anxiety leads to undesirable life outcomes (Hayes et al., 1999, pp. 151–152).

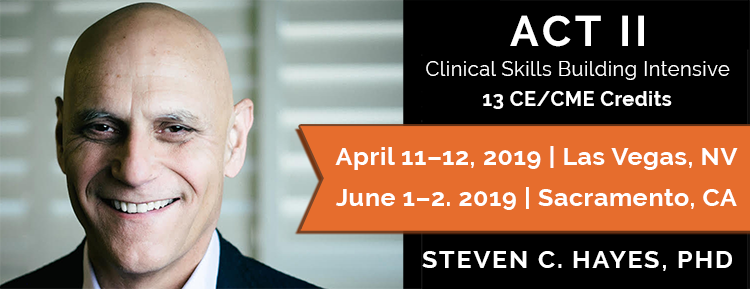

Learn How ACT Can Transform Your Life and the Lives of Your Clients.