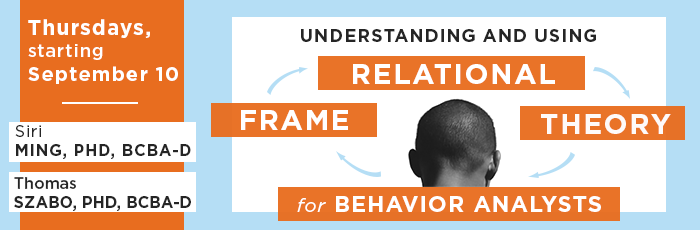

Author: Siri Ming, PhD, BCBA-D

For behavior analysts working with children with autism, taking a relational frame theory (RFT) perspective fundamentally shifts the focus of our language programming.

Understanding RFT allows us to view the development of complex verbal behavior, including the development of a sense of self, as learning to respond to increasingly complex relational patterns. With this lens on our work, we can approach language intervention from a truly functional standpoint, setting the foundations for generative language from the very start.

These foundations include naming and equivalence, as well as laying the groundwork for numerous other relational framing repertoires by establishing contextual control over non-arbitrary relational responding, across multiple response topographies, before shifting into arbitrarily applicable relational patterns of responding.

When working in early intervention, we have the chance to assess and establish relational responding repertoires from the ground up. However, very young children and early learners of all ages pose a few complicating issues that aren’t always highlighted in experimental research papers—after all, university student subjects are unlikely to respond to stimuli like Charlie, the infant subject in Lipken, Hayes & Hayes’ classic study did, which he “picked up, chewed, or threw on the floor” (1993, p. 210). And even if our learners don’t eat our stimuli during training, they almost certainly do not have already well-generalized and fluent repertoires. So, we must be sure to take into consideration what factors may support their responding during assessment, in order to get a better sense of what the operant level truly is. After all, we wouldn’t assess a child’s level of imitative skills by putting them in an advanced Zumba class!

From decades of research both in stimulus equivalence as well as RFT, we know that there are a number of factors that make demonstration of derivation or transformation of function more likely. Anyone working with young children knows that motivation and maintaining instructional control is critical for teaching, and the same is true for assessment.

Other factors include:

- mixing auditory and visual stimuli (as is the case in natural language interactions)

- using relevant instructions and not training too many relations at once

- using familiar or meaningful rather than abstract stimuli

- creating as a familiar context (while still controlling for learning histories)

For these reasons, before assessing how well-generalized learner repertoires are with respect to abstract stimuli and unfamiliar contexts (as might be seen in programs for building fluency, such as Cassidy & Roche’s SMART training—essentially an expert ballet class for relational training), we recommend starting with a few more familiar, real-life stimuli, in familiar and motivating contexts.

At the earliest levels of equivalence, that might be relating pet animals to their names and sounds. For same vs different, we use animals that like the same or different foods from one another. In comparison training, we use gems from craft stores that are worth more or less than one another. And for opposite we use cookie jars that are empty or full, or monsters that are big or small.

See also: Connecting Relational Frames to Human Suffering

In all your work with young learners, remember that they are children first. Use fun, meaningful content and contexts—and don’t worry too much if your cards get a little chewed on!

Learn Skills to Establish Generative Language in Early Intervention Programs.